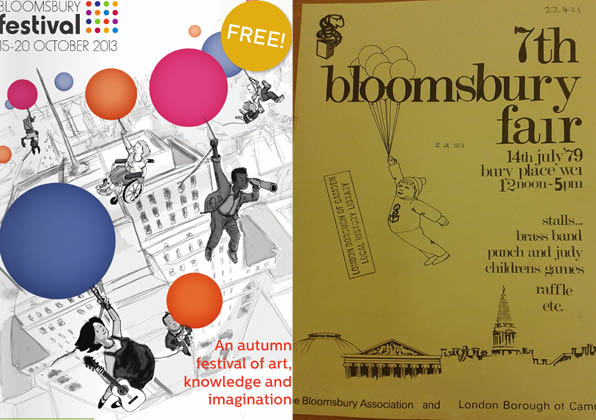

Poster C/O Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre & the Bloomsbury Association

It’s the Bloomsbury fair, not the Bloomsbury Festival!’ Such was the reaction of one of my research participants upon our arriving at her flat with the Bloomsbury ‘Festival in a Box’ a couple of weeks ago. This participant is now in her late nineties and has lived in central Bloomsbury since the Second World War. Still living alone in a flat in not far from my own work place, she is just one of several participants whom I have encountered during the Festival in a Box project who has managed—in a way that now seems almost unimaginable—to have lived and raised a family in the very heart of London. She remains as a living custodian of the kind of life and kind of memories that come from this experience.

As we introduced our project and showed this participant some flyers from the 2013 Bloomsbury Festival—billed as ‘an autumn festival of art, knowledge and imagination’—we were met with the same response again and again: ‘It’s the Bloomsbury fair. It was never called the Bloomsbury Festival, never!’ Her reaction was vehement, almost violent on this point, and not for the first time during this project I was self-conscious of worrying at a potentially troubling or painful memory.

The visit, and then visits, continued, and over the course of these a relationship developed that allowed us to find out more about her long life in the area, the stories that have shaped and emerged from this life, and allowed us too to engage her in various art activities, from literary readings to ceramics workshops.

She told us stories about coming to Bloomsbury during the Second World War, about passing time in Bloomsbury Square during and in-between pregnancies (‘tummy big, tummy less big’) and about teaching her children to walk on the smooth floors of the King’s Library in the British Museum –‘all my children learnt to walk there’.

It emerged too that, in addition to raising a family in the area, our participant had been heavily involved in community life in Bloomsbury, and an active member of the Bloomsbury Association. Among other things, it emerged, she had been instrumental in organising a recurring event called the BloomsburyFair. Hence her insistence in rejecting our claim that we had come to conduct research with the Bloomsbury Festival. She was not herself at first able to give us much detail on the Bloomsbury Fair, merely that it was an event intended to provide a focal point for the local community and to draw them together. Armed with the name of this event, however, I was drawn back to the Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre to see if I could discover more.

In the archive I found two posters one from 1975 and one from 1979, along with a programme for the Bloomsbury Fair from 1978. One of these posters caught my eye. Its design: a child being lifted off its feet by a handful of balloons, with the Bloomsbury landmarks of St. George’s Church and the British Museum in the background, was uncannily similar to the design used for the 2013 Bloomsbury Festival programme, designed independently decades later to show children floating on handfuls of balloons in front of Senate House. Same idea. Same aesthetic. Different generations. It seems significant in this light that the 1978 programme uncovered alongside the poster spoke of rising rents in the area putting local shops out of business, and of the need to ‘protect Bloomsbury via an active association’

Posters from the 1979 Bloomsbury Fair (courtesy of Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre and the Bloomsbury Association) and the 2013 Bloomsbury Festival

This story, of our active link to the Bloomsbury fair as well as the posters and the programmes found in the archive, encapsulates for me something significant about the Festival in a Box project. It illustrates how a network of collaborators and institutions—artists, researchers, participants, a local studies archive, a contemporary arts festival—can come together, in sometimes unusual formations, to respect a significant lost or semi-lost narrative of place. It demonstrates the wealth of the stories and the memories retained (if perhaps in fragmentary form) by socially isolated people with the dementia, and what might be gained from accessing these.

The contemporary Bloomsbury Festival, along with the University of London itself, might it seemed to me be able to learn from this earlier event, and its mission to protect and preserve Bloomsbury as a viable space of community. The two similar posters from these events speak of a correspondence across time: of similar threats and concerns facing those struggling to live in central London, and of an established, continuing role for art and culture, for festivals and for fairs, in combatting those threats.

Recent Comments